Avoiding the AI Complexity Cliff

Managing scope in AI-assisted development

In AI-assisted development, LLMs would ideally understand everything there is to know about our codebase, interpret any instructions, and answer any question with the full context of the project. After all, context is king, especially with LLMs. But most real-world projects are too large and complex for that to be even remotely feasible.

A typical enterprise application might contain more than 200,000 lines of code across 1,500 files. That’s roughly 800,000 tokens before documentation, build configuration, or tests. Even a million-token window can’t hold it all. But capacity isn’t the real constraint. Models start degrading long before they hit the limit.

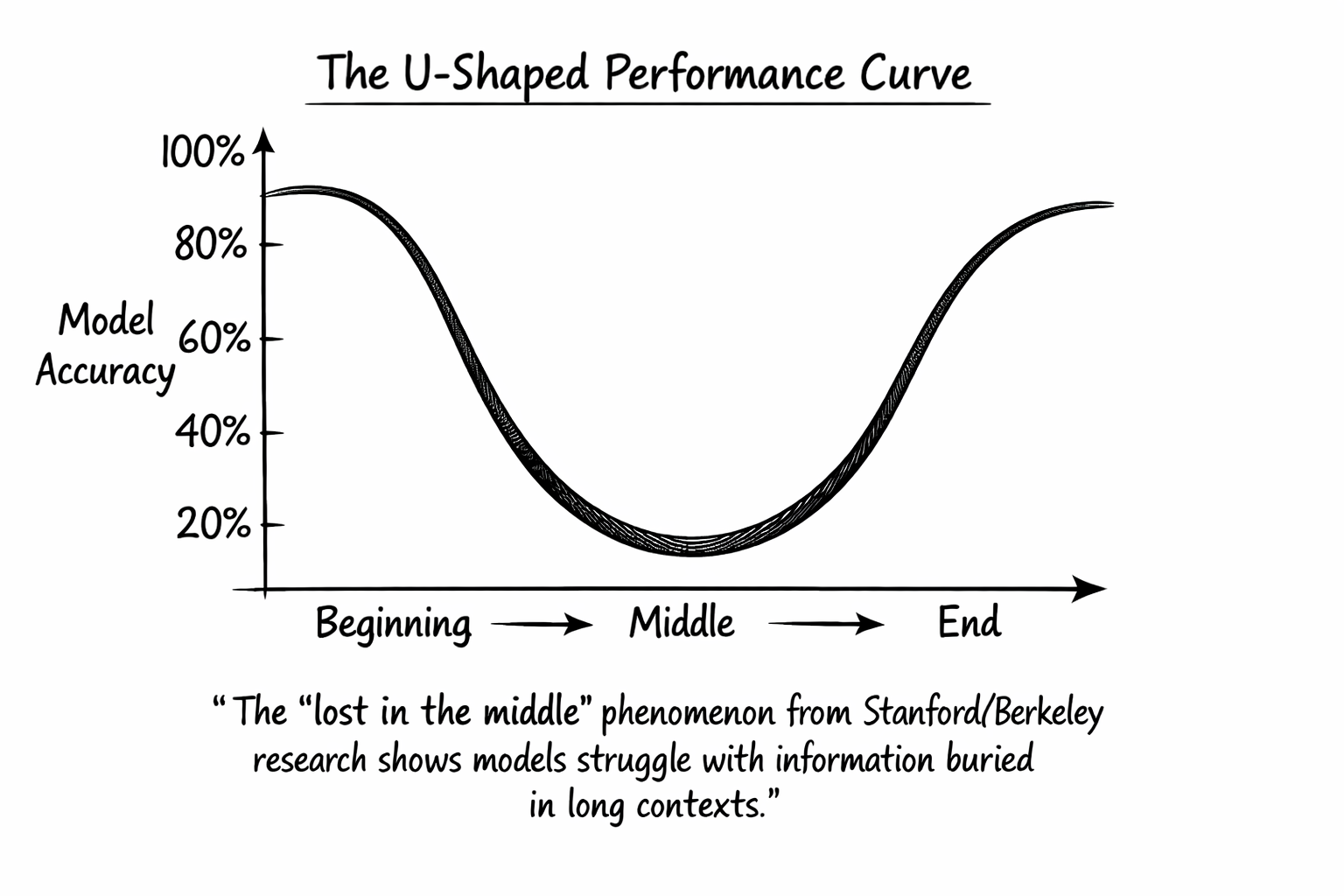

Research from Stanford and Berkeley identified what they call the lost-in-the-middle phenomenon: LLMs perform best when relevant information sits at the beginning or end of the input context, with significant degradation when models must access information buried in the middle. Performance follows a U-shaped curve, favoring primacy and recency while struggling with everything between.

Practitioners have noticed this gap between advertised capacity and effective use. Dex Horthy at HumanLayer popularized the term “dumb zone” in his presentation “No Vibes Allowed: Solving Hard Problems in Complex Codebases” to describe the region where LLM reasoning degrades as context usage grows past 40-60% of maximum capacity. A model claiming 200K tokens becomes unreliable around 130K. The threshold isn’t a gradual decline. It’s a cliff.

We can’t just feed in context and hope for miracles. Every token competes for the model’s limited attention budget. What we include matters. When we include it matters. The order in which we present information matters. Context engineering becomes as important as the prompts themselves.

Three Patterns, One Problem

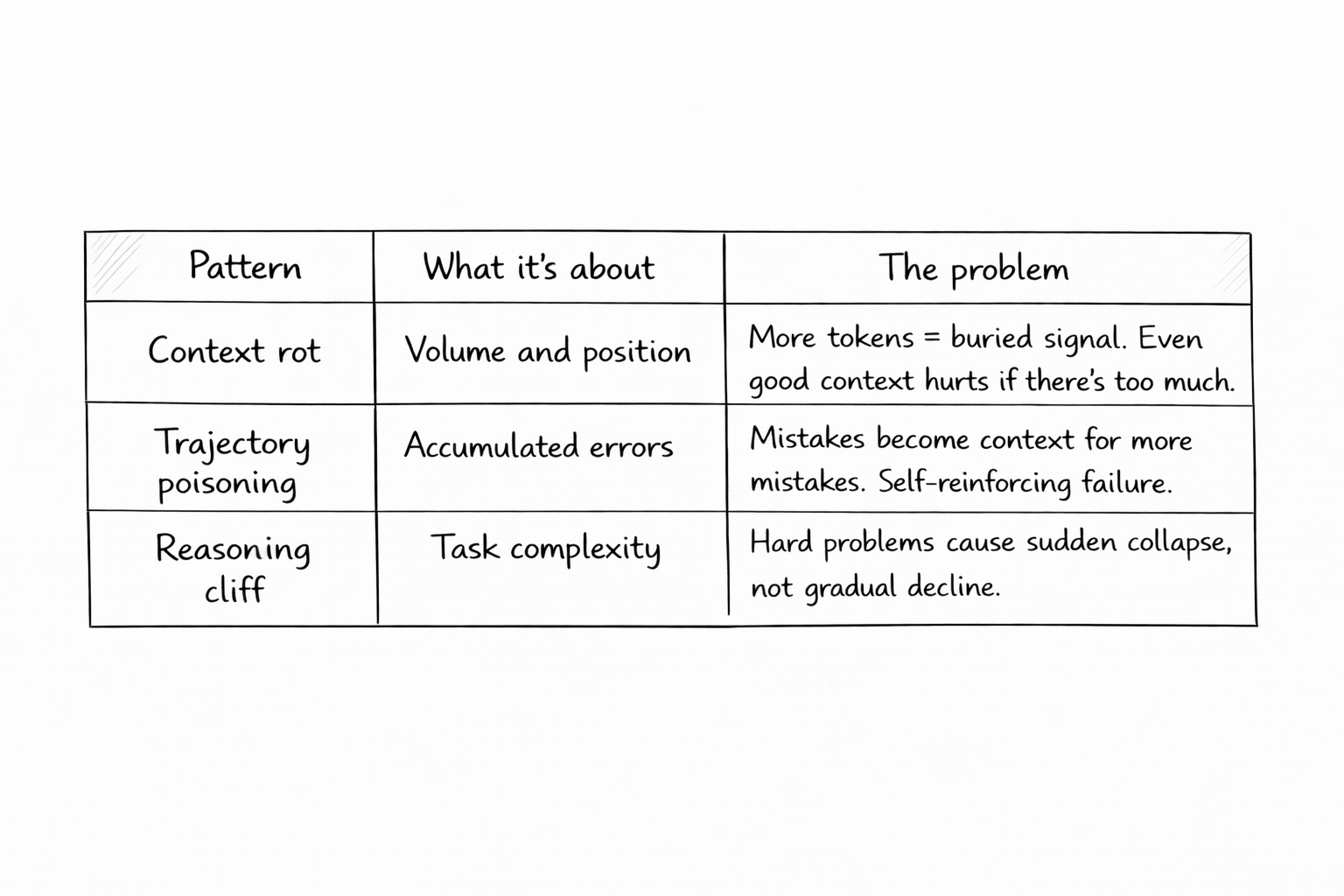

What makes AI-assisted development challenging isn’t any single limitation. It’s the interaction of three related patterns that compound as work complexity increases. Understanding these patterns is essential for knowing when to push forward and when to start fresh.

The first is context rot. This is about volume and position, not task difficulty. As you add more tokens to the context window, the model’s ability to find and use relevant information degrades. The culprit is attention: every token competes with every other token. Add 10,000 tokens of background code, and the 500 tokens that actually matter get harder to locate.

Chroma Research documented this effect systematically. Information buried in the middle of long contexts gets missed, even when it’s exactly what the model needs. Related-but-irrelevant content is worse than random noise because it looks relevant enough to distract. The practical result: you can make a model perform worse by giving it more context, even when that context is accurate and related to the task.

The second, and often most damaging in practice, is trajectory poisoning. When an AI coding session goes wrong, the errors don’t just disappear. They become part of the context the model uses for subsequent reasoning. The model references its own mistakes. Attempts to correct them introduce more confusion. Failed approaches, abandoned code paths, and accumulated misunderstandings pollute the working context until the model gets stuck in patterns it can’t escape.

There is no course correction that can fix the context. Once a trajectory goes bad, the context is poisoned. Every subsequent interaction draws on that polluted history. The model confidently builds on flawed foundations, producing output that looks reasonable but compounds the original errors.

The third is the reasoning cliff. This is about task complexity, not context size. As problems require more reasoning steps or involve more interacting variables, model accuracy doesn’t decline gradually. It collapses.

Apple’s GSM-Symbolic research documented this threshold systematically. Adding a single clause that seems relevant to a math problem caused performance drops of up to 65% across all state-of-the-art models, even when that clause contributed nothing to the solution. The models aren’t reasoning through the problem. They’re pattern-matching, and extra complexity breaks the pattern. The practical result: you can’t fix a task that’s past the cliff by prompting better. You have to simplify the task itself.

These patterns interact. Context rot makes trajectory poisoning more likely. Poisoned trajectories push tasks past the reasoning cliff. The compound effect explains why AI-assisted development can feel so inconsistent: sometimes brilliantly helpful, sometimes stubbornly wrong in ways that resist correction.

Diminishing Returns

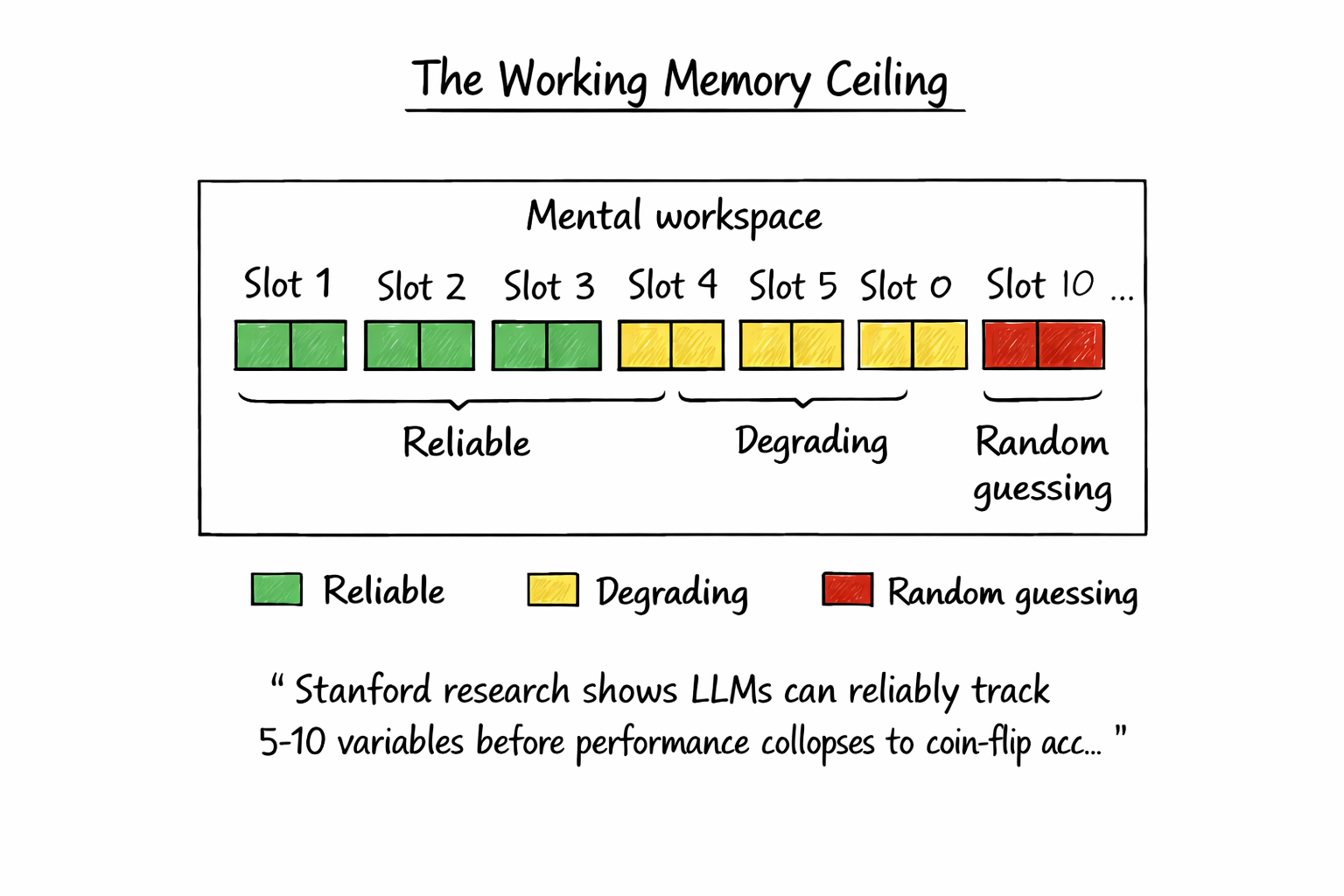

These phenomena share a common root. Transformer attention scales quadratically with sequence length. Every token must be compared with every other token, so doubling context length quadruples computational cost. But the problem isn’t just compute. The model’s ability to maintain meaningful relationships across vast token distances degrades even when hardware handles the load.

Apple’s research revealed something counterintuitive: when problems become very difficult, models actually expend less reasoning effort. Their internal heuristics signal diminishing returns, so they give up rather than trying harder. Stanford researchers found similar limits on working memory. LLMs can track at most 5-10 variables before performance degrades toward random guessing.

Don’t assume that because an answer is computable from the context, an LLM can compute it.

Managing Complexity

The temptation when hitting these limits is to wait for better models. Larger context windows. More sophisticated reasoning. The tools improve constantly. This approach misses the point.

Addy Osmani captures it well in his LLM coding workflow guide: scope management is everything. Feed the LLM manageable tasks, not the whole codebase at once. Break projects into iterative steps and tackle them one by one. Each chunk should be small enough that the AI can handle it effectively and you can understand the code it produces.

This mirrors good software engineering practice, but it’s even more important with AI in the loop. LLMs do best with focused prompts: implement one function, fix one bug, add one feature at a time. If you ask for too much at once, the model is likely to produce low-quality results.

Keep Tasks Small and Focused

Keep the problem scope narrow enough that you can hold the entire context in your head. If you can’t explain what the AI should do in a sentence or two, the task is too big. Split it.

Provide only the context the AI needs for the current task. Dumping your entire codebase into context doesn’t help. It actively hurts by filling the effective working space with noise.

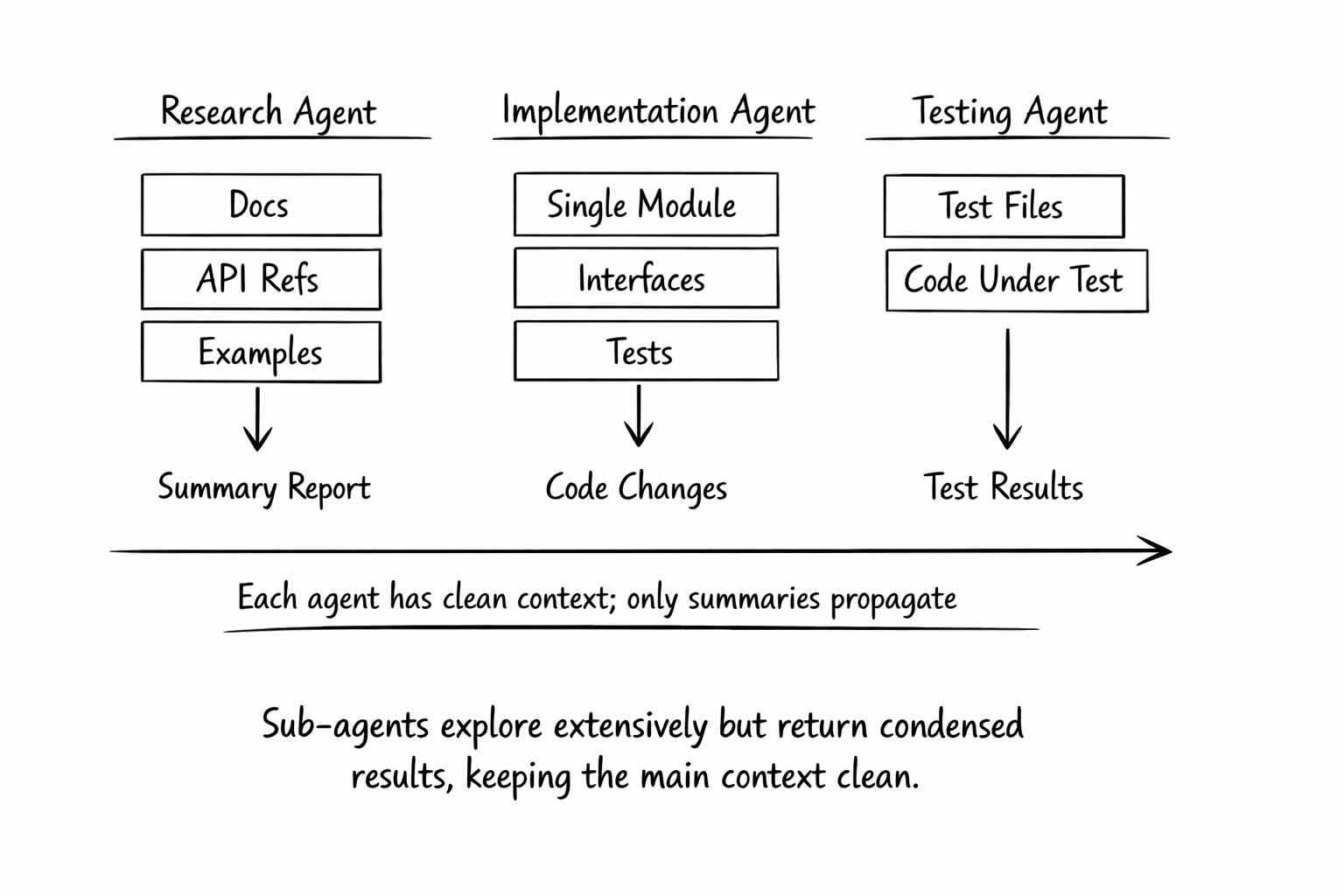

Use Subagents to Scope Context, Not Define Roles

Agents aren’t just about role-playing different personas. Their real value lies in constraining which context is loaded at each step of work.

A research agent pulls documentation and API references. An implementation skill loads only the module being modified. Testing skills focus on test files and the code under test. Anthropic’s context engineering guidance explains this pattern: rather than having a single agent maintain state across an entire project, specialized sub-agents handle focused tasks with clean context windows.

The subagent pattern works because each step operates with focused context rather than the accumulated noise of everything that came before. Think of skills and subagents as context boundaries, not personality changes.

Clear Context Between Tasks

One of the most practical lessons from production AI coding is to start fresh when output quality degrades. The “poisoned trajectory” problem is real.

Once an AI session goes wrong, the errors become part of the context. The model references its own mistakes. Attempts to correct them introduce more noise. The context fills with false starts and abandoned approaches.

The fix is simple. Commit your work, close the session, and start a new one with a clean context. Treat sessions like git branches. When one goes sideways, abandon it rather than trying to salvage the accumulated mess.

Session hygiene matters more than most practitioners realize. The teams getting consistent value from AI tools have developed strong instincts about when to start over rather than push through degraded output.

Engineering Judgment Still Required

Waiting for the models to fix the problem is a losing strategy. The alternative is treating scope management as a core skill. Decomposing complex problems into focused tasks isn’t a workaround for tool limitations. It’s the practice that makes AI assistance genuinely useful.

This shouldn’t be surprising. Breaking complex problems into manageable pieces was always good engineering practice. We just didn’t notice how much we relied on human ability to infer meaning from an ambiguous context. Humans read a vague ticket, pull in relevant knowledge from memory, ask clarifying questions, and still produce coherent work. LLMs can’t.

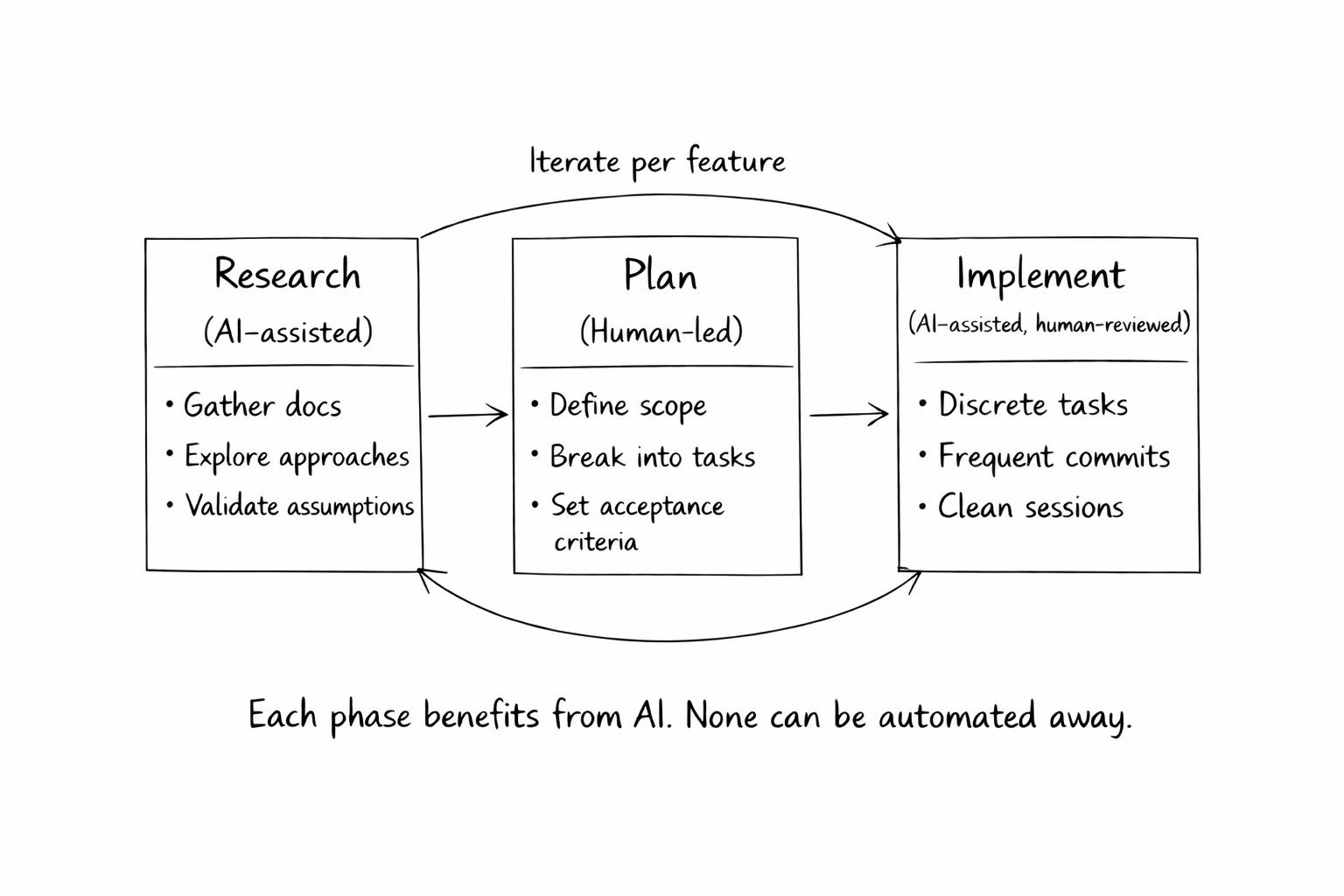

Adherence to a structured SDLC that was optional in a pre-AI world becomes essential when your implementation partner takes instructions literally and forgets everything between sessions. Processes like Spec-Driven Development or Research Plan Implementation (RPI) are tailored for working with coding agents. Each phase benefits from AI assistance.

We can’t completely outsource engineering to LLMs. Keeping humans in the loop is critical. Humans are still far more efficient at inferring meaning, managing context, and interpreting ambiguity. It is human ingenuity that is necessary to design the systems, make judgment calls, and decompose problems into chunks that fit within the effective working zone. That work can’t be automated.

The tools improve constantly. The constraints I’ve described will shift. But the fundamental concepts hold. AI amplifies engineering capability rather than replacing engineering judgment. The complexity cliff exists. Working deliberately within their boundaries is how you get value from these tools without drowning in confident-sounding mistakes.